For over two decades, Wicked has transported theatre audiences into the untold story behind The Wizard of Oz (1939). Bringing its magic to the screen required a spectacle that not only honoured its Broadway origins but expanded beyond them. Among the many key collaborators in this transformation was Industrial Light & Magic’s Pablo Helman, production visual effects supervisor. In a recent conversation, Helman shares with ILM.com the challenges and triumphs of adapting this theatrical phenomenon for film, seamlessly blending practical techniques with cutting-edge visual effects to create an enchanting cinematic experience.

By Jamie Benning

The Musical Challenge

Helman admits that working on Wicked (2024) was an entirely new experience for him compared to his experiences on films like the Star Wars prequels (1999-2005), The Irishman (2019) and The Fabelmans (2022). “I think I was ignorant, in that I thought for the last 30 years that my job started with the images and ended with the images,” he tells ILM.com. “Normally music is something that happens later on. But with this movie, not only is there pre-recorded material but there is live singing. And there’s connections that are being made between the actors while they sing. Things that change between them that makes them elicit other reactions. And you’re there three feet from the action with the music happening. That translated into how we approached the visual effects. It makes all the difference.”

But understanding how to integrate those effects meant first understanding director Jon M. Chu’s vision.

Getting into Jon M. Chu’s Head

Helman is known for his thorough preparation when working with directors, and his collaboration with Jon M. Chu on Wicked was no exception. “It’s my job to get into the director’s head,” he says. “When I first interviewed with him just to see how we would click, I did a lot of research on him as a filmmaker. How does he use the cameras, camera movement, lighting, sequencing, editing—all of it. So we basically had the same language because I kind of cheated a little bit. I made it my business to understand how he goes about his process.”

He explains that Chu’s methodology is unique. “He has an incredible vision for the movie, and then he’s open enough to let the movie happen to him. Sometimes the movie develops in a way that is unexpected, and it grows in a specific way or something happens, and then he says, ‘I never thought of it this way. Look, that’s great. We have options.’

“The funny thing about it is that once the project concludes,” Helman continues, “a little bit of their filmmaking stays with me as a kind of a tool set of things, that once in a while I pull out, and that helps me with something else. Every director is different. Everybody has a different process of understanding the storytelling.”

Unlike directors who rely heavily on previsualization, Chu prefers a more fluid, organic approach, embracing spontaneity throughout the filmmaking process. “He doesn’t use pre-vis the way some directors do,” Helman says. “We’d sit at a table with the heads of department, with Alice Brooks (Director of Photography), Myron Kerstein (Editor), with Nathan Crowley (Production Designer), Paul Corbould (Special Effects Supervisor), Jo McLaren (Stunt Coordinator) with a model of the set for that scene. And then we give him a little stick with a little Elphaba and other characters and he goes in and shows us what the scene is about. And when there is music, he plays the music from his phone. Then he does the movement of the actors with Chris Scott, the choreographer. And so we video those sessions and then we all go away and try to figure out how we’re going to achieve Jon’s vision—between all of us.

“I did a lot of listening, because I hadn’t worked with Jon before,” Helman continues “And Jon and Alice and Myron kind of grew up together from school, and they have been working together. And so for me to come in, it’s like, are they going to let me in? And they opened their arms and let me in. And it was a wonderful experience.”

Building Oz: The Role of Practical Sets and the Practicalities of Shooting a Musical

Nathan Crowley’s elaborate practical sets played a crucial role in grounding Wicked’s fantastical world. Helman reflects on how these sets benefited both the cast and the visual effects team. “You want to chase the truth as much as possible,” he says. “Yes, there were nine million tulips planted, but they were planted a hundred miles from the set. But there are benefits.”

He elaborates on the process of blending the practical and digital elements. “There’s a shot in the beginning, of kids running through the tulips towards Munchkinland, and the matte line is around the kids. You know, after that, it’s all visual effects. Is it useful? Yes, for the actors, they have something there. But we changed the lighting, added the sun, and completed the tulips in post. The final look is a collaboration.”

The barley fields posed another challenge. “We planted real barley, but during the first take, you couldn’t run through it—it was too dense. We had to shave it down and then digitally replace everything to maintain the illusion.”

Helman explains that the scale of the production meant nearly every frame of the film required some level of visual effects intervention. “There are 2,200 visual effects shots in the movie. So every shot is a visual effects shot. Because this is a musical, all the actors are wearing really big earpieces that had to be replaced in 3D. There were also mics on their chests.”

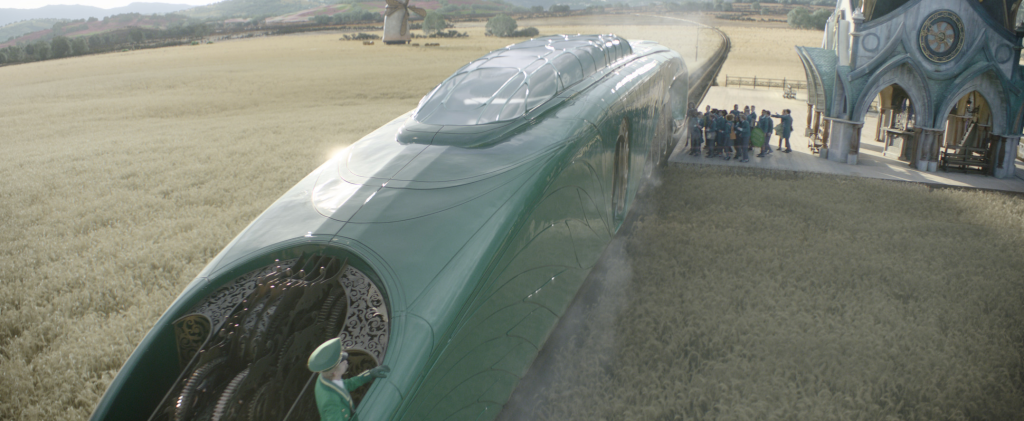

The scale of the sets also dictated when practical elements could give way to digital enhancements. “The interior sets go up to 25 feet and the exterior sets go up to 55 feet and then after that we take over as visual effects,” says Helman. “Special effects were really big too.Paul Corbould and his team built a huge train. But the gears were not moving. So that’s where visual effects lends a hand. And the gears under the train are visual effects. And the inside of the train is visual effects because there was a small section built, but not the whole thing.

“And then the train was very reflective,” Helman continues “So if the camera follows it, then you have the reflection of all the lights and everything else that had to be recreated and painted out. So yes, there is a combination of reality and not reality. It’s a realization that we are creating an illusion, all of us. And we all contribute little by little to that illusion. And then in post, we put it all together and complete it.”

Striving for Authenticity: Cynthia Erivo’s Green Transformation

Helman and his team explored multiple approaches to achieving Elphaba’s distinctive green skin, testing a range of methods to determine the best solution. “Yes, we did a lot of testing,” he recalls. “We did different tests of what would happen if we used green makeup, what would happen if she didn’t have makeup, but we were there to fix everything that couldn’t be done.”

Ultimately, it was actor Cynthia Erivo herself who made the final decision. “Cynthia said, ‘I need to be green. I think I need to be that person,’” Helman explains. “And I know it’s three hours in the chair, but I need to put in that time to become that character. And it made a difference, I think.”

Even with practical makeup, the visual effects team played a crucial role in refining the look throughout the film. “We still have visual effects in every shot,” Helman says, citing the long shooting days, the strain of makeup on Cynthia’s skin, and even the challenges of contact lenses. “She had contacts. And I knew from other experiences like The Irishman that after a while the contacts start moving and the actor starts looking cross-eyed. So we had to fix all kinds of things.”

Additionally, subtle digital enhancements were required for continuity. “The makeup went to the middle of the lip, but not into her mouth, for obvious reasons. So, as I said, we had to adjust every shot,” he adds.

Flying Monkeys and Magical Transformations

One of the many visually striking sequences in Wicked is the transformation of the flying monkeys. Helman describes the scene as both challenging and rewarding. “It’s almost a horror scene. The monkeys are in pain, their wings breaking through their backs. It’s unnatural, which adds to the horror,” he explains. “We used feathers flying around to give a sense of atmosphere and depth. The horror of it had to be mitigated somehow. So there were times when we went too far. There were times when we didn’t go far enough. And then we all kind of adjusted.”

Helman emphasizes the importance of storytelling in visual effects. “There’s the fact that these monkeys need to fly away in like four shots. So how do you tell that story in its specifics in four shots? They need to get the wings, try them, and then be either successful or not. And so all that stuff is storytelling. It’s part of what we do in visual effects. The animation team led by David Shirk did a great job.”

Grounded Magic

Magic is, of course, central to Wicked, and Helman’s team took a deliberately subtle approach to its visualization. The Grimmerie posed unique challenges. “It wasn’t really thought out when we were shooting,” he admits. “Most of the time, Cynthia was in front of a blue square, gesturing as directed. But we ultimately made it so that the words became golden, with pages moving. It feels tactile and grounded, not over-the-top. We weren’t going for that kind of fantastical thing, because it’s been done before. Even if we were doing a visual effect, it had to look practical.”

Elphaba’s imperfect spellcasting in this scene also adds another layer to her character. “Due to her inexperience, she’s not very good at casting spells. Every time she does, something bad happens,” Helman says. “It’s relatable—magic grounded in imperfection, just like life.”

Defying Gravity: A Pivotal Sequence

The “Defying Gravity” sequence is a pivotal scene bridging the two films, requiring a seamless blend of practical stunts and digital effects. “Cynthia performed many of her own stunts, including being flown on wires and complex rigs,” says Helman “We’ve seen people flying before. You could just have somebody being wired in and you can say to that person, now you’re moving right, now you’re moving left, left to right and right to left. But those kinds of things don’t work. Cynthia was being flown 200 feet around the blue-screen set, singing! She is really trying to keep herself from the forces that are trying to throw her in different directions. And you can really see that she’s doing it. That contributes to the reality of the visual effects work we do.”

Helman also highlights Elphaba’s emotional arc in her final scene through the use of light and symbolism. “You start from the bottom in the darkness towards the light and you go out on the balcony towards the sun, and then the sun starts coming down throughout that sequence towards the end of the movie. If you have seen the play, you know that at the end of the first act, the cape gets bigger and bigger. So the question is, how do we translate that? Do we do it? Is it going to be laughable? The cape is a visual effect, because we couldn’t use a real one due to the wires. Throughout that sequence, everything becomes pictorial. And by the time we get to that shot, basically, it’s a spiritual, religious picture. The clouds are very Renaissance Italian, with the sun behind them and there’s all kinds of volume shadows and volume light coming through. And then all of a sudden you realize, oh my goodness, the cape is huge. What happened? Are you inside her mind, or is that a literal thing? Probably not. And then she does the war cry and the camera pulls back out and you think the movie ends, but she turns around and goes away flying. And then the audience is thinking, ‘wait, wait, where are you going?’ Then the movie ends to get them ready for part two.

“But all those kinds of things are not by coincidence,” Helman adds “They’re each thought out in terms of structural storytelling, building expectations.”

The Collaborative Spirit

The scale of Wicked was immense, involving contributions from more than 1,000 visual effects artists across five countries, ILM in San Francisco and Sydney as well as teams at Framestore, OPSIS, Lola, Outpost and TPO. Helman is quick to credit the teamwork behind the film’s ambitious visual effects. “We’re working together for three years to make these movies. And so I’m really grateful to all of them. Robert Weaver and Anthony Smith were the ILM visual effects supervisors, and David Shirk was the animation supervisor. Great collaboration and lots of fun.”

Helman is philosophical about the creative challenge. “On set sometimes you get into some arguments or differences. Or as Jon calls them, ‘offerings.’ Sometimes you say, ‘I’m offering you this solution, or you can go this way or we can go another way.’”

This cooperative effort was essential on a production as challenging as Wicked. “It’s 2,200 visual effects shots, but every department played a role in making the world of Wicked believable,” Helman explains. He highlights the importance of working closely with Nathan Crowley, Alice Brooks, Paul Corbould, and the rest of the team.

“Alice, Jon, and I talked a lot about it,” Helman says. He describes how lighting played a crucial role in integrating visual effects with the cinematography. “The lights were on the set, but we removed them. If you look at a movie that was shot in the ‘50s, there’s a certain look to it, but you have to achieve a certain look from behind the camera. But that’s not so anymore. You can put light sources wherever you want. And if you’re careful with them, when you remove them, there is no such thing as unjustified lighting.”

By ensuring that visual effects supported rather than dictated the cinematography, the team was able to create a seamless blend of practical and digital elements.

A Lesson in Artistry

For Helman, Wicked reinforced his philosophy that “visual effects shouldn’t be impeding anything. Whatever the director wants to do, wherever they want to put the camera—that’s what we’re there for, to encourage that kind of storytelling.”

The grueling 155-day shoot, filmed in continuity across both parts, pushed the cast and crew to their limits. Helman acknowledges the toll such a long production can take: “After day 70, it’s like everybody’s done. It’s like, elbows are out—‘Get out of my way, why are you looking at me like that?’ Those kinds of things happen.” But despite the fatigue, the shared vision kept the team pushing forward. It is a long project, but it’s a good thing because it gives you kind of a sense of not worrying about anything else, but what you have in front of you.”

The audience’s response helped reaffirm the purpose behind the work. “It’s one of those pictures that I had to go to the theater to hear the people’s reactions. I usually don’t do that. But this one I did, and it reminded me of why we do what we do, which is to make art that is being shared.”

Reflecting on the experience, Helman expresses gratitude for the people who made it possible. “You can have a great project, great people, or great financial satisfaction—if you’re lucky, you get two out of three. But the most rewarding part is the collaboration. At the end of the day, it’s about the people you work with.”

As Wicked continues to enchant audiences worldwide, Industrial Light & Magic’s artistry stands as a testament to the power of collaboration and innovation in storytelling.

Learn more about ILM and Wicked on Lighter Darker: The ILM Podcast.

—

Jamie Benning is a filmmaker, author, podcaster and lifelong fan of sci-fi and fantasy movies. Visit Filmumentaries.com and listen to The Filmumentaries Podcast for twice-monthly interviews with behind-the-scenes artists. Find Jamie on X @jamieswb and as @filmumentaries on Threads, Instagram, Bluesky and Facebook.