Heads still roll 25 years later in the Tim Burton classic Sleepy Hollow (1999). Revisit all of the eerie magic behind Industrial Light & Magic’s work that brought Washington Irving’s folktale to life and reintroduced audiences to one of cinema’s greatest on-screen monsters, the headless horseman.

By Adam Berry

On October 5th, 1949, the Walt Disney Studios released a feature film that reimagined two classic pieces of literature through the guise of The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (1949). While the first half retells the whimsical story of Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows (1908), it is the second half that left a long-lasting impression on young audiences as they were introduced to American writer Washington Irving’s eerie folktale, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow (1820).

Released just in time for Halloween that year, this feature would go on to be recognized as one of Disney’s classics due to its memorable songs, beautiful animation, and the unforgettable visualization of Irving’s ghostly antagonist, the headless horseman. The unsettling imagery of a headless man riding horseback with a sword in one hand and a flaming jack-o’lantern in the other allowed the legend to evolve as film versions were passed down to new generations. 50 years later, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow would once again evolve on screen, and explore the story in new ways, re-introducing audiences to Irving’s horrific tale of the undead horseman.

To take this classic into a tangible world, a highly imaginative and visual mind was necessary to capture the fantastical elements of this story while rooting it in a sense of reality. Tim Burton, director of such films as Beetlejuice (1988) and Edward Scissorhands (1990), was keen to step in as he was a fan of the Disney film. Burton told American Cinematographer, “I was really familiar with the original story because I’d seen the Disney cartoon…. I actually didn’t read the source novel until after I had read the script.” Burton’s own history with Disney, including attending the California Institute of the Arts on a Disney scholarship, and working at Walt Disney Studios as an animator on projects such as The Black Cauldron (1985), destined him to take on the challenge of creating a fresh retelling of Sleepy Hollow.

Burton’s vision was to create a fantasy world that felt real in which the headless horseman could exist. The aesthetic needed to emulate, but not copy, the atmosphere of the classic Hammer Studios horror films such as Dracula (1931) or Frankenstein (1931) with their moody and gothic tones that left the audience in a state of unease. With that being said, Italian director Mario Bava’s Black Sunday (1960) was the core inspiration for the film, giving Sleepy Hollow (1999) a classic movie feel while adding elements that were pictorial and synthetic.

To achieve his vision of what Sleepy Hollow needed to look like, Burton knew there had to be a balance between the use of traditional special effects and digital visual effects. “Digital technology is very interesting and certainly has its place in filmmaking, but when you’re watching a movie like Black Sunday you really feel as if you’re there,” said Burton. While he was resistant to using visual effects at first, he relied on the artists at Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) to help realize the full scope of his vision, particularly when it came to bringing the headless horseman into existence as a living, breathing creature.

ILM visual effects supervisor Jim Mitchell was tasked with solving how the horseman could exist in the film as a real man without having to rely on older methods. Tricks like having the coat propped up on the actor’s shoulders didn’t work as the proportions were wrong, eliminating the appearance that the horseman was indeed a man. Mitchell said, “Tim and I knew that something just wasn’t going to be right with that approach. We eventually decided that our Headless Horseman would be an actual person riding the horse and flailing his axe around, except that we’d just digitally erase his head.”

The most complex shots for ILM involved removing the horseman’s head. There were about 300 horseman shots altogether, with ILM creating 220 and London’s Computer Film Company contributing the rest. To convincingly convey that the horseman was real, the ILM team innovated a special blue hood for stunt actor Ray Park to wear during action sequences that the ILM artists could later isolate and erase from the shot. Blue was used as it is easily keyed from the plate so the effects team could restore the background in place of the head.

To fill the space where the actor’s head was taken out, a clean background plate of the sequence was shot, but the artists noticed that one element was still missing as the horseman has a large cape with a collar around his neck. “It was not only necessary to replace the background where his head would have been, but to also make a digital collar in the computer that was then matched to his movements,” shared computer graphics artist Sean Schur in Paramount Pictures’ Behind the Legend documentary. By using actors and replacing heads digitally, the horseman presents as a living and breathing creature.

Achieving this effect was particularly challenging during fight sequences with actors Johnny Depp and Casper Van Dien as their faces would be blocked out by the horseman actor’s blue hood. Once ILM erased the horseman’s head, they would also have to go back and eliminate the other actors’ heads as well. Mitchell shared, “I would have Johnny or Casper go through the same actions without the Horseman in there, and we’d just put their head into any frames where the horseman’s head was blocking theirs. It’s a tricky process, but it was actually pretty effective.”

Equally as challenging were the beheading scenes throughout the film. Creature effects artist Kevin Yagher created prosthetic heads of the actors for use in these pivotal moments while ILM was able to digitally recreate the scene using a series of three plates to blend together and form one cohesive shot. Using the scene in which the menacing Lady Van Tassel (Miranda Richardson) decapitates her bewitching sister as an example, Richardson would be filmed going through the motions of swinging her axe to dead air, then the prosthetic head flying off the body of her sister would be filmed separately, and finally the digital capture of that scene would be created. Once all three plates were finished, ILM would blend these together to make a seamless sequence for each beheading, making it feel all the more real for the audience. This was not an easy task for the artists as the film has ten decapitation sequences.

Burton wanted to convey suspense and a sense of impending doom throughout the film and tasked ILM with a series of subtle visual effects shots that added to the unsettling feeling when the horseman would appear. Most notable is the disturbing scene where the horseman pursues a family at their home. Killian (Steven Waddington) sits at his table with a crackling fire, which spontaneously erupts into larger flames seconds before the horseman crashes down the door. Sequence Supervisor Joel Aron shared, “I took the skull, which is the headless horseman’s skull, so I pulled up the eyebrows giving it this demonic look with a strong forehead, curling up the corners of the mouth and bringing the jaw around to continue to sculpt what would be the fire so that I knew when the fire would come off it would have an irregular shape.” It’s a blink-and-you-will-miss-it effect, but if you look closely you can see 13 demonic faces emerge within the flames in a quick flash which is meant to indicate that evil is present. It’s so subtle that it was intended for audiences to question whether they really saw the faces or not.

Natural elements were also added and utilized to punctuate the horseman’s presence. The subtle introduction of thick fog and flashes of lightning appear every time the horseman gallops toward his next victim in pure cinematic fashion. Sleepy Hollow was shot mostly on location in a small town called Marlow, just outside of London, which meant the environment presented Burton with an ideal setting for the gloomy atmosphere. These elements could be viewed by some as cheap tricks in a major film but the use of heavy smoke for fog makes the atmosphere more haunting and interesting. “In the Western Woods set and at some of the other locations, you can definitely see the smoke – it looks like the fog they used in the old Frankenstein and Mummy movies,” said director of photography Emmanuel Lubezki.

While using smoke allowed the filmmakers to get a consistent movie look, it presented challenges for the ILM team as once they were finished adding actors’ heads back into the shots they would also have to build back in the foggy backgrounds and natural elements in each scene. “The big problem for us was [that] every shot involving the horseman also had lightning and fog,” explained Jim Mitchell, “which was constantly moving and always changing, as opposed to trees and buildings, which are rigid. Whenever lightning hit the Horseman, we had to make sure that when we replaced his collar or any other parts of his suit that his head was blocking, we put the same lighting effect on it.”

To simplify this, Mitchell asked Burton and Lubezki to shoot the scenes as though the actors’ heads were already removed despite the level of complexity it would add for the ILM team to ensure the elements moved organically with the actors as they rushed through the fog, or horse hooves galloped through the settled leaves on the ground. “There are all kinds of things we’d prefer to stay away from when we’re doing this type of work, but if you lose those [atmospheric] touches, all of a sudden it’s not the same sort of visual, and it doesn’t have the same power,” concluded Mitchell.

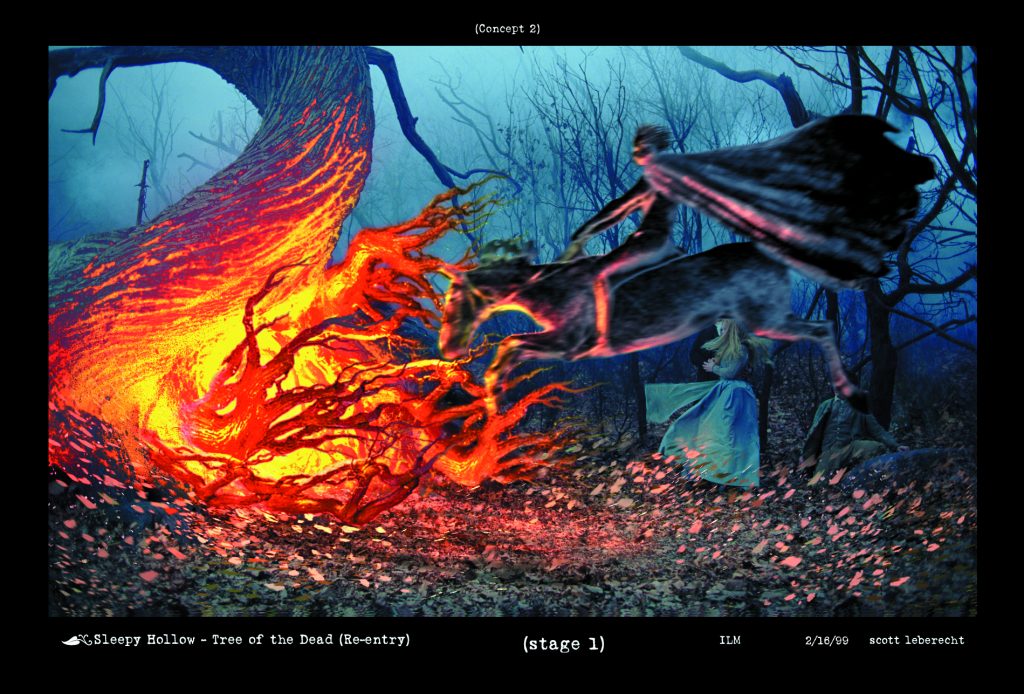

This is especially apparent during a highly intense scene mid-film when the protagonists discover the tree of the dead, which is the horseman’s resting place and gateway to hell. The combination of the natural elements like fog and tree leaves with digital effects cemented the believability of this scene as the horseman enters from the base of the tree in a bloody and terrifying fashion. There were multiple plates used to build this effect. Firstly, a blue screen plate of the horse and jumping rider was shot. Next, a background shot of the forest environment, with the tree of the dead and actors standing close to where the horse emerges. Finally, a shot of the fog and leaves being disturbed creates the effect of the horseman jumping out of the tree. ILM didn’t have a bluescreen shot of an actual horse, so they had to create one in the computer, as well as the headless horseman, which are both digital elements. Similarly to the decapitation sequences, artists layered all of these separate plates on top of each other to form the singular shot making a scene that might have been unrealistic feel very believable instead.

It has been 25 years since its initial theatrical release, and rewatching Sleepy Hollow you can witness firsthand how ILM’s work remains timeless and able to reach new generations. The eerie and suspenseful atmosphere that Sleepy Hollow pulls audiences in and stands as a formidable achievement of classic Hollywood filmmaking, adding another iconic cinematic monster with the headless horseman, who is equally as feared standing next to other horror icons such as the unnerving Count Dracula, and misunderstood Frankenstein monster. Washington Irving’s The Legend of Sleepy Hollow lives on through the visionary work of artists from each generation. For Burton’s retelling, ILM wielded the eerie magic that gave life to the undying legend of the headless horseman.

—

Adam Berry is the Studio Operations Manager for the ILM Vancouver studio. His passion for film led Adam to ILM in 2022, coming from an extensive career across different sectors of the hospitality industry including cruise ships, luxury hotels and resorts. If he’s not at the movies or traveling to new destinations, you can find Adam staying active and exploring Vancouver.