The ILM Vancouver artist details her globe-trotting career path from special make-up effects to art direction to effects supervision.

By Lucas O. Seastrom

For decades, a significant aspect of Industrial Light & Magic’s company culture has been defined by the atmosphere in dailies. These routine sessions where the effects team reviews work-in-progress and provides feedback are common across the industry, but ILM has always prided itself on its distinct style that encourages open and equal communication. Tania Richard had spent some 15 years working in visual effects before she joined ILM in 2018 as an art director at the Vancouver studio. And as she puts it, “ILM’s collaborative dynamic really shines in dailies.”

While working on Space Jam: A New Legacy (2021), Richard was at first surprised when visual effects supervisor Grady Cofer would call on her in dailies, seemingly at random. “Grady wouldn’t hesitate to call my name out and ask me what I thought about something, even if it wasn’t something I was working directly on,” Richard explains. “He valued everyone’s opinion, and made you feel part of the overall process. Earlier in my career at other studios, dailies was pretty quiet and you didn’t speak up very often. Everyone has their own way of approaching things in dailies, but at ILM it’s always with the intent of creating a collaborative experience.”

As ILM has continued its global expansion – which now includes studios in Vancouver, London, Sydney, and Mumbai, in addition to its San Francisco headquarters – seasoned professionals from across the effects industry have joined the ranks. Each brings their unique experience working on diverse projects and often in many different types of roles. Richard is no different.

Growing up in Sarnia on the southern border of Ontario, Canada, Richard had what she describes as a creative upbringing. Both of her parents had their own artistic pursuits, and her mother in particular encouraged Richard and her brother (now a storyboard artist) to make careers out of their passions. Though she aspired to work in filmmaking from her time in high school, Richard chose to study traditional fine art while studying at McMaster University southwest of Toronto. “But I was lucky in that the university also had film theory courses,” she notes, “so I studied film theory as well as fine art.”

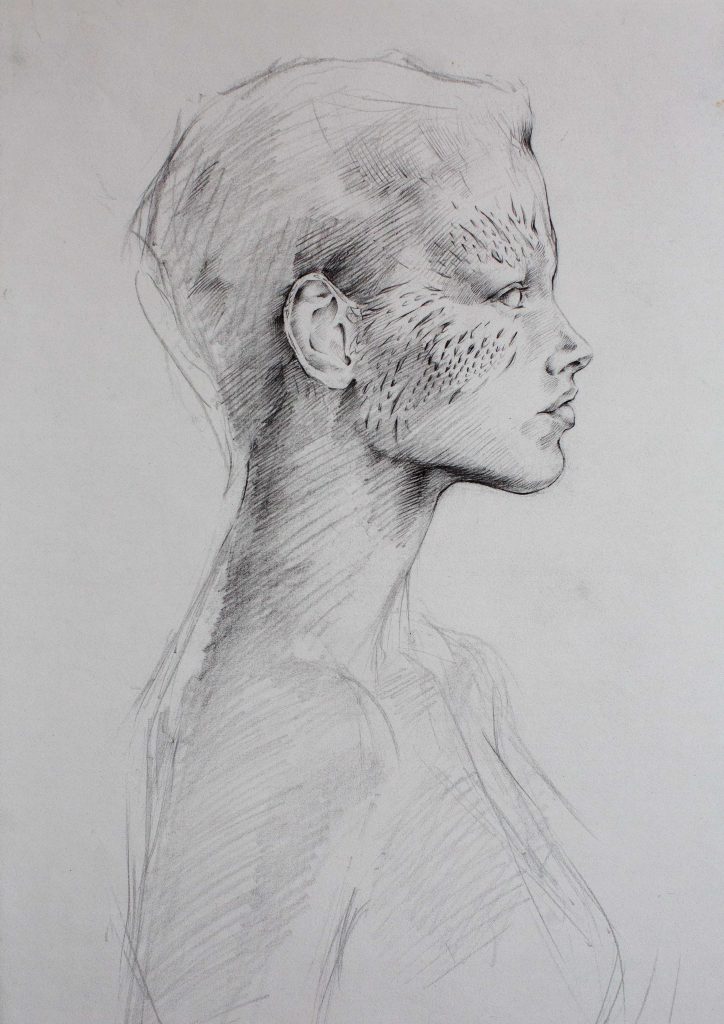

With this unusual blend of disciplines, Richard was able to both learn academic theories and create artworks that attempted to realize them in aesthetic form. She studied sculpture, drawing, print-making, art history, and painting, as well as film theory. Her fascination with the concept of film spectatorship inspired her to focus in painting. “There was a film theorist, Laura Mulvey, who talked a lot about the male gaze in spectatorship,” Richard explains. “I studied her a lot, as well as Cindy Sherman, who would often photograph herself in these film-looking environments and settings. I ended up doing something similar where I’d start by creating these film stills, photographing myself dressed up in various situations, and using that as reference for my paintings.”

To this day, Richard is fascinated by the intersections of artistic craft and theory, in particular the way that filmmakers code their works. “It can almost be a language, a communication between the filmmaker and the audience,” she says. “Somebody like [Andrei] Tarkovsky puts these little codes throughout his filmmaking, whether it’s sound like dripping water or a cuckoo, or a visual like apples. They were all meaningful to him on a personal level. You see and hear these codes throughout all of his films, and if you were familiar enough with them, it was almost as if he was talking to you in a way, on another level.”

At ILM, Richard has worked with director Shannon Tindle on both Lost Ollie (2022) and Ultraman: Rising (2024), and she describes the filmmaker along similar lines. “He’ll reference the same films in his creative process, like Kramer vs. Kramer [1979], for example. He loves that film, and I’m aware of that because I’ve worked with him long enough and had enough discussions with him to know that when I see something in the way a frame is composed or an animation performance in one of his films, I can understand where his influence is coming from. It’s special. It makes you feel like you’re connecting with the filmmaker on another level.”

As she finished her undergraduate studies, Richard jumped into work at Toronto-based FXSMITH, a special effects company founded by innovative makeup designer, Gordon Smith. Initially thinking she’d be working on a local television show, Richard soon discovered their team’s assignment was the feature film X-Men (2000). Initially, Smith had his new hire drawing concepts for characters requiring prosthetics, and as production commenced, Richard was part of the on-set team creating the extensive make-up for Rebecca Romijn as Mystique.

“It was a great experience and I had my foot in the door,” says Richard. “But this was back around 1999, and the transition from practical effects to computer effects was happening. For X-Men, we worked closely with the visual effects team on set because they had to pick up a lot of our work in post-production and refine it. In talking to some of the crew there, they encouraged me to move into visual effects.”

Richard’s brother was then studying classical animation at Toronto’s Sheridan College, a school that had graduated a number of artists later hired by ILM. “If the Sheridan opportunity hadn’t worked out, I might’ve gone for a PhD in film theory,” Richard notes. Joining the school’s postgraduate visual effects program, her main professor was Richard Cohen, recently returned from a stint at ILM as a CG artist on Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) and Death Becomes Her (1992).

“There were about 12 of us in the class, and Richard [Cohen] felt that rather than having us all isolated and doing our own thing, we should make a short film together,” says Richard. “If I had not done that, I might’ve focused more on the animation side. But on the group project, we leaned into each other’s strengths, and because I had a painting background, it was clear that I was the concept artist, matte painter, and designer on the team. I did do some animation, but I learned that it wasn’t my strength.” She adds that although she intended to create traditional matte paintings for their film (ultimately titled The Artist of the Beautiful), Cohen urged her to learn Photoshop and embrace the emerging computer-based tools.

As she finished her studies at Sheridan, Richard had already begun professional work, initially as a concept designer for 2003’s Blizzard under production designer Tamara Deverell. She then became a digital matte painter at Toybox, a local effects house that was soon acquired by Technicolor. Eventually, a former colleague invited her to come to Sydney, Australia where Animal Logic was developing the animated feature Happy Feet (2006). “I was young and up for the big move, so I said yes,” Richard comments. “That was back when ‘2 ½ D’ projections were the thing, so I did a number of those mattes on that feature.”

During this period, Richard encountered a number of important mentors, among whom was the late visual effects producer Diana Giorgiutti, with whom Richard served as a concept artist on Baz Luhrmann’s Australia (2008). “We were on location in Darwin and Bowen for something like seven to nine weeks,” Richard explains. “Di had me working directly with [production designer] Catherine Martin. She had me sitting with editor Dody Dorn for a week. Dody had cut Memento [2000]. We were together early on when she had voice recordings of the actors reading the script and she wanted some images to cut in with them. I’d be mocking up frames for her and she explained to me the compositions they needed. She was really generous with her time.”

Soon, London-based Double Negative came calling, and Richard spent nearly a decade in the United Kingdom working on everything from Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2 (2011) to Interstellar (2014). As visual effects art director on Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them (2016), she again found an important mentor in production designer Stuart Craig, who’d overseen the visual development of the entire Potter franchise. After creating elevation and sectional drawings for sets, Craig tasked Richard with building digital mock-ups, and together they’d determine the preferred camera angles for which Richard then created detailed concepts.

“Stuart had worked with set designer Stephanie McMillan for many years,” says Richard, “and they would often go onto set together and shoot the space in black and white. That helped them analyze the composition before they started adding color and texture, which only came after they were happy with the black and white composition. When I built my models, I rendered them in black and white as well, so I was approaching it instinctively in a similar way. Stuart loved it and helped me understand why it was a good approach. Rather than going full-tilt and adding lots of texture and detail right from the beginning, you start to learn that actually you might never see a particular area because of the way it’s being lit, or something like that. You learn to focus in an efficient way on where to add that structural detail, where to hit the image with color to have the most impact. It was a brilliant lesson from Stuart.”

A return to Animal Logic for 2018’s Peter Rabbit was Richard’s ultimate springboard to ILM. With the opportunity to work closely with director Will Gluck, visual effects supervisor Will Reichelt, and associate visual effects supervisor Matt Middleton (the latter of whom are both with ILM now), she came to realize that effects supervision was her chosen path. “Will [Reichelt] had me run lighting dailies and look after the assets while he was busy on set,” Richard explains. “I was also really involved in the DI process and had a team of artists who I delegated a lot of design work to, so in many ways, it felt like a natural transition.”

In early 2018, the ILM Art Department’s creative director David Nakabayashi and senior producer Jennifer Coronado convinced Richard to make another move, this time back to her native Canada to work at ILM’s Vancouver studio. It was a significant decision, as Richard was then considering a move to New Zealand for a brief respite from active work. But the opportunity to join ILM was too important to pass up.

“ILM was the pinnacle,” Richard says frankly. “For anybody who is around my age and grew up with Star Wars, you see ILM as the height of where you want to be in the industry. But I wasn’t sure I had what it took to be a part of the company, so it was a surprise when they reached out. I barely took any time off between working on Peter Rabbit and coming to ILM.”

Initially working as an art director, Richard describes her first impressions of ILM as “overwhelming, exciting, and different.” After assisting Vancouver’s creative director Jeff White on some initial project bids, she was soon working on Disney’s Aladdin (2019). “The ILM Art Department is incredibly talented and is really the best of the best,” Richard notes. “There’s so much you can learn from them.” She continued as an art director on Space Jam: A New Legacy, for which ILM was responsible for integrating the classic Warner Brothers animated characters with live action footage.

“There was a lot of artwork created at the beginning of Space Jam,” Richard explains. “The spirit of it evolved quite a lot over the course of the show. I had a wonderful team, and I really loved working on Bugs Bunny! [laughs] Grady Cofer had me doing paint-overs on some of the characters, which I really enjoyed. The whole team was involved in refining the final looks of each character, including the textures crew, the groom artists, the modeling team, and the animators. I’m always blown away when I see animation come through.”

It was after Space Jam that Richard made the transition to associate visual effects supervisor on Lost Ollie. “I’m a bit like the righthand person or wingman for the visual effects supervisor,” she elaborates. “We work very closely with production and our department leads and supes to help establish looks, refine shots, and execute what needs to be done in post to maintain a certain level of quality and consistency. I had been slowly navigating into an effects supervisor-type role for a while, but I wasn’t sure if I had all the skillsets to be able to do it. I talked to Jenn and Nak about it, and they were very supportive and helped to guide me into this position along with Jeff White and [executive in charge] Spencer Kent.

“I think I just got really lucky,” Richard continues. “I believe that Jeff had Ultraman in mind for me, but it wasn’t quite ready yet. [Visual effects supervisor] Hayden [Jones] and [visual effects executive producer] Stefan [Drury] were working with Shannon Tindle on Lost Ollie, so I had a chance to establish a relationship with the same client. I think that’s why they thought it might be a good starting point for me. It was a smaller project, and I love the hybrid between live action and CG characters. It’s probably what I’m best at and what I love to do the most. I ended up diving in heavily on two episodes, and then I stayed in the background on the final two because that was when I started transitioning to Ultraman: Rising.”

The move into supervision has allowed Richard to focus more on refining her approach to communication and collaboration between the artists and the clients. “On Ultraman, Hayden was great at encouraging the team to ask questions and offer up suggestions with Shannon,” she notes. “What’s great about Shannon is that he creates an environment where it’s okay to suggest something that might not ultimately be the right idea, but it’s great to put it out there and see if it works. [ILM executive creative director] John Knoll is very similar. He embraces that exploration and isn’t afraid to try something.”

Richard emphasizes that “part of being a supervisor is having an ability to read the room and understand the personalities of the artists and how they like to communicate.” And as an artist herself, Richard brings her own unique blend of experiences. “I’ve been lucky to have had a toe in the practical side of things very early on. I’ve also worked with some really talented people who come from an earlier generation of filmmakers. I hope that some of that knowledge translates in my communication with the artists. Both Grady and Hayden like to do quick paint-overs on things in dailies, and that’s something I like to do as well. If words don’t quite explain something, sometimes a quick drawing or paint-over can act as a visual reference. Many supes like to do that.”

As so many have attested, it’s the people that have truly made the difference at ILM in its 50 years of storytelling. “Have curiosity about the people you’re working with,” Richard says, “and have empathy for them. Try to understand where your colleagues may be at a certain point in time. You can use that to develop relationships throughout your career, which is so important.”

Read more about Richard’s work on Ultraman: Rising here on ILM.com.

—

Lucas O. Seastrom is the editor of ILM.com and a contributing writer & historian for Lucasfilm.