Exploring the technical innovations and behind-the-scenes stories that brought Slimer to life in Ghostbusters 2, reaching new heights in animatronics and practical effects at Industrial Light & Magic.

By Jamie Benning

When Ghostbusters (1984) premiered, it became an instant classic. With a star-studded cast—Bill Murray, Dan Aykroyd, Harold Ramis, and Ernie Hudson—alongside Sigourney Weaver, Rick Moranis, and Annie Potts, the film combined supernatural elements with groundbreaking visual effects and perfect comedic timing, captivating audiences worldwide. The film grossed $282 million in its initial theatrical run, cementing its place in film history.

Beyond the popular human cast, one standout element was the ghost originally named “Onionhead.” Special effects artist Steve Johnson, credited as the sculptor, likely drew inspiration for the name from its vegetable-like appearance. This gluttonous green ghost, classified as a Class 5 Full-Roaming Vapor, made a brief but memorable appearance that delighted audiences. Designed to be grotesque and chaotic, Onionhead unexpectedly became a fan favorite. Bill Murray’s famous line, “He slimed me!” as Peter Venkman, became one of the most quoted phrases of 1984. Onionhead’s popularity only grew with The Real Ghostbusters (1986) animated series, where he was reimagined as a mischievous yet lovable, pet-like character.

In the eleventh episode of The Real Ghostbusters, titled “Citizen Ghost,” which first aired in November 1986, Onionhead finally got his new name. The episode’s flashback shows how the Ghostbusters became friends with the little green ghost, with Ray Stantz giving him the fitting nickname “Slimer.” The name endured, becoming a permanent fixture in all subsequent Ghostbusters projects.

Ghostbusters 2 (1989) sought to bring the evolved version of Slimer to the big screen, balancing the charm of the original character with the expectations of younger fans familiar with the cartoon. With the baton passed from Boss Film Studios to ILM for the sequel, visual effects supervisor Dennis Muren described the task ahead of them to Cinefex. “We had the opportunity to create a whole new array of ghostly images,” he explained, using all the tools at their disposal. An early idea of using a rod puppet was quickly dismissed, with Muren preferring to opt for a fresh take on the “man in a suit” approach.

With the technological advances made in the five years since the original film, the goal was not just to capture the original magic but to push the boundaries of animatronics, puppetry, and practical effects.

Reimagining Slimer

For the sequel, Slimer needed to embody the more playful, cartoonish persona. “[Executive Producer] Michael [C. Gross] wanted elements from the cartoon version incorporated as well, and to this end he had Thom [Enriquiez] do the new series of drawings – which were fabulous,” creature and makeup designer Tim Lawrence explained to Cinefex.

Mark Siegel, a key contributor to Slimer’s original creation, was brought to ILM for Ghostbusters 2 to resculpt the character and adapt him for the film’s lighter tone. Siegel had been deeply involved in the creation of the original Onionhead ghost, sculpting his teeth, tongue, and inner mouth, as well as the complete replacement head for a second puppet with a wider, more frightened look to the mouth. He also puppeteered the tongue and eyebrows for the majority of the shots.

The sculpting process for the design maquette was a collaborative effort, with Siegel primarily handling Slimer’s body, head, and face while fellow crew member and performer Howie Weed focused on the arms and hands. For the full-sized puppet Siegel sculpted the head and the arms.

The character of Onionhead in Ghostbusters wasn’t just an arbitrary creation. His mannerisms and chaotic energy were directly inspired by the late John Belushi, specifically his portrayal of Bluto in Animal House (1978). This connection was not merely symbolic; it was a tangible part of his design and performance. Mark Siegel recalls how Harold Ramis and Dan Aykroyd made it clear to the team that Slimer was a representation of their close friend Belushi’s comedic spirit.

The team didn’t just envision this; they meticulously pored over Belushi’s scenes. “We studied frame by frame old VHS tapes of Belushi’s Animal House scenes, focusing on his expressions,” Siegel elaborates. This analysis allowed them to incorporate Belushi’s signature movements and broad, exaggerated physicality into Slimer’s performance for the first film. According to Siegel, it was Belushi’s expressive style that truly captured the blend of charm and grotesqueness that defined Slimer’s character.

“When I first started sculpting the new Slimer, I thought, ‘Well, that’s cute,'” Siegel admits. But the evolution of the character, from disgusting blob to family-friendly ghost, presented some challenges. “I felt we were losing some of the raw, chaotic energy that made Slimer memorable in the first film.”

The sculpting process was a collaborative effort, with Siegel primarily handling Slimer’s body, head and face while fellow crew member and performer Howie Weed focused on the arms and hands.

Scenes originally envisioned for Slimer in Ghostbusters 2 included him eating various types of food around the station house while Louis (Rick Moranis) tried in vain to catch him. Then later, when Louis straps on a backpack and tries to help the Ghostbusters, he finds Slimer driving a bus. Louis hitches a ride and the two eventually become friends. An early storyboard also shows Slimer flying around the Statue of Liberty for the final shot of the movie, mirroring the first film’s finale. But, as is often the case in artistic pursuits, things were adapted, changed, and even removed along the way, all for a multitude of reasons.

Technical Innovations: Pioneering Animatronics

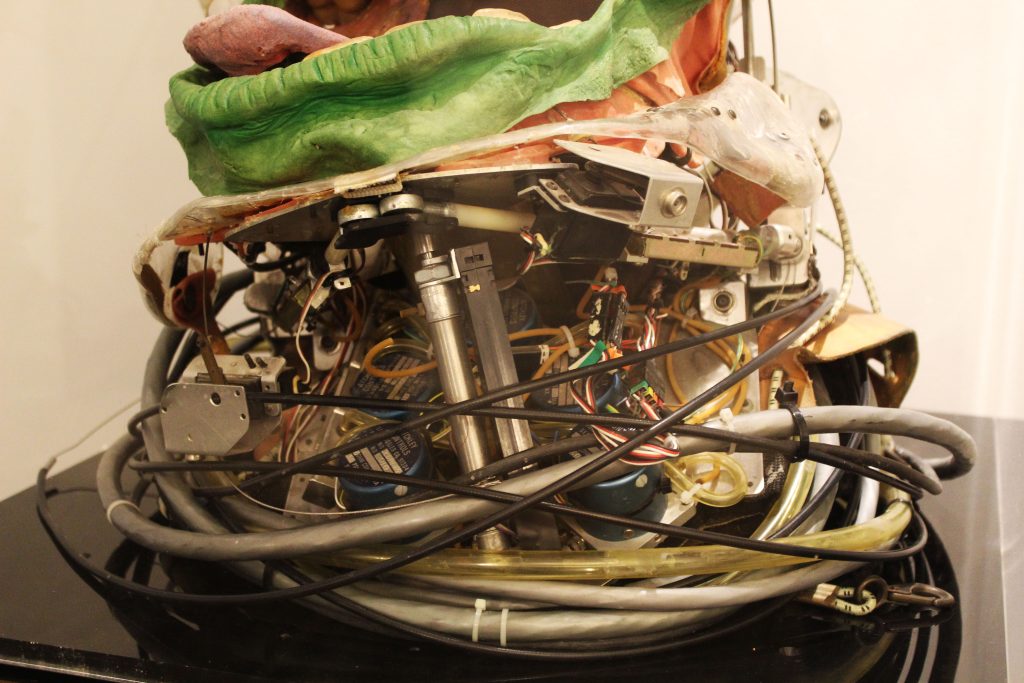

One of the key advancements in Ghostbusters 2 was the shift from manual cable-controlled puppetry to the use of radio-controlled servos for Slimer’s facial expressions. Al Coulter, an ILM animatronics engineer, led the effort to remotely automate Slimer’s face, allowing for more nuanced performances. “Al wanted to mechanize Slimer’s expressions,” Siegel says. “The SNARK system (reported as both Serial Networked Actuator Relay Kit and Synthetic Neuro-Animation Repeating Kinetics module) allowed us to control multiple servos simultaneously, meaning that expressions could be achieved more easily, with fewer people.” This system was a technological leap forward, offering new possibilities for nuanced expressions, though it brought its own set of challenges.

One of the key motivations for this advancement was to streamline post-production, which had been a challenge in the original film. “In Ghostbusters, we had to deal with puppeteers in the frame, which meant removing them during post-production,” Siegel recalls. That was both time consuming and costly.

Coulter notes that while the servos were originally designed for consumer RC airplanes, significant customization was required to make them work for Slimer’s facial movements. “The joystick stuff from Hobby World caused a lot of problems when we went onstage, because there was so much interference from all the lights and the wires and the machinery…that we needed to be able to connect our character to something direct, hardwired. So we had this guy build control boards which we bundled together and plugged into a PC. And that PC would then have software on it, custom again, and it would record our performance.” It was a major advancement for the time, in a way following in the footsteps of the leaps ILM had made in motion-control in the mid 1970s for the spaceships in George Lucas’ Star Wars: A New Hope (1977).

Coulter reflects that working with the technology of the time, particularly the slow computing speeds, was a challenge in itself. “We were working with computers that ran at 24 MHz—slow by today’s standards, but cutting edge at the time.” Despite this, the SNARK system was a pioneering achievement in real-time, computer-controlled puppetry, allowing for repeatable and detailed performances. “The facial expression, eyebrows, eyes, I think we had a nose wiggle…being updated to radio control servos, that was a great idea,” Siegel adds.

Behind-the-scenes videos posted by William Forsche (another crew member) show the incredible range of facial contortions that could be achieved with the new Slimer, from sad to happy to curious in a matter of seconds. While motion-control’s precision was essential for the spaceships in Star Wars, it wasn’t yet clear how well the recording and playback of Slimer’s facial movements would work.

Ultimately the servos introduced their own set of challenges. While the system allowed for greater control, it limited some of the more exaggerated movements that defined the original Slimer. As Siegel explains, “In the first film, Slimer’s jaw was controlled manually, allowing for more exaggerated, chaotic movements. The sculpture was extremely soft and flexible. There was no structure in the lower jaw at all. Just a little metal rod in the lower lip and a puppeteer down below could pull it, just stretch that rubber way wide, twist it from side to side and get a whole variety of expressions, make him chew and stuff…. While the servos and pneumatics we used in Ghostbusters 2 gave us more precise control over the facial expressions, they also introduced limitations in terms of flexibility and range.”

The head wasn’t the only challenge. In trying to replicate the exaggerated, cartoon-like appearance and movements of Slimer’s body from the animated series, the crew encountered more hurdles.

Innovating Slimer’s Body Design

While the animatronics used for Slimer’s facial expressions were groundbreaking, if beginning to become troublesome, the team also had to experiment with new ways to animate Slimer’s body. Tim Lawrence proposed constructing the body out of spandex with bean-bag-like filling, aiming to give Slimer a more fluid, exaggerated range of motion similar to the stretch-and-squash effect seen in his cartoon form.

However, this idea quickly ran into practical issues, as Siegel explains. “It might have been a couple of days before we were shooting and Dennis Muren came in and looked at the whole puppet assembled, and he wisely said well that spandex is going to look entirely different on camera than that rubber head. For some reason that had never occurred to anyone before. So in a mad rush we took that spandex bean bag body into our spray ventilation booth, and I had to mix up big batches of foam latex and we actually spatulated it onto that entire body. And that’s really hard to do because the foam latex has a limited time before it sets. And then it had to be baked in an oven. So it was thrown together at short notice in less than one day. When the rubber was cured over the bean bag it made the body a lot less stretchy and flexible than Tim had intended it to be.” The problems were beginning to mount.

Robin Shelby: The Heart Inside Slimer

While ILM envisioned the technological advancements to play a key role in bringing the reimagined Slimer to life in Ghostbusters 2, it was Robin Shelby (then Robin Navlyt), the performer inside the suit, who truly embodied the character’s spirit.

Previously known by ILM for her role as a troll in Ron Howard’s Willow (1988), she took over the role of Slimer for Ghostbusters 2 after the original actor, Bobby Porter, became unavailable. As Shelby recalls, “They had someone cast, then they wrote Slimer out of the script…and then they wrote him back in, but the original actor had taken on another project.” At just 20 years old, Shelby was tasked with bringing a new version of Slimer to life, despite the suit’s heavy and cumbersome design. But she was up for the challenge!

“I grew up doing musical theater, a lot of dance. So I was very aware of my body…and that helped a lot. I didn’t have any stunt experience at the time, but a lot of movement and dance experience,” remarks Shelby. Reflecting on her first impression of the suit, she adds, “They were still building it when I came in. It wasn’t all painted and set. They had to do a cast of my face and head so they could fit it to me. But when I first saw it with the motors, it was a little scary. The weight was extraordinary. But, the crew was amazing.”

With Shelby performing inside the suit and the expressions operated remotely, production became more efficient. By using a bluescreen and having Shelby wear a black leotard, ILM eliminated the need for puppeteer removal in post-production, just as originally planned.

Shelby and the team had about five to six weeks of rehearsal to help her adjust to the suit and coordinate with the puppeteers operating the animatronic features. The suit itself came in three interlocking segments: the main body, the gloves for the hands and arms, and the head. “I couldn’t see anything really. So what we would do is rehearse, they would shoot it, and then they would have me watch it. So I could see what it was all looking like. So, I knew in my head what we were all doing,” Shelby explains.

The physical demands of the suit were intense. Al Coulter praises her resilience, noting that the weight of the suit left marks on her nose: “As soon as you said action, she was right back there, just banging it out every time. Amazing!”

“The suit was probably over a third of my own body weight,” Shelby recalls. “I probably weighed like 95 pounds when we shot that, and it was probably 35 pounds. People ask, was it hot? It was hot, but probably the worst part of it was the weight.”

Michael C. Gross, the executive producer, visited the set to see how Shelby’s performance was going. “He said, ‘Don’t be the dancer that I know you are, just get in there and be gritty and be mean. Just go out and have fun.’ So I was just trying to rough it up a lot on the set, make it not so dainty or perfect or dance-like, just to try and make it work for the character. It was so much fun, and they really allowed me to play with it,” Shelby enthuses.

Still, even enthusiasm has its limits. “We’d worked for about an hour, and they’d say, okay, we’re gonna take a break. They’d take the head off. I wouldn’t get out of the costume, but they’d take the head off so I could have water, get some air, and sit down. There was a time that I pushed it because we were in the middle of the scene and I didn’t want to stop. They’re like, ‘Are you okay? You’re alright?’ I’d say, ‘Yeah, yeah, let’s just keep shooting. We’re almost done.’ And then Tim is directing me, ‘Okay, Robin, we need you to turn around and go left. Robin? Robin!!’ And I wasn’t even answering. ‘Get her out,’ they shouted.

“You try to be the trooper…when you’re new and just want to please everybody. But lesson learned, yeah, absolutely,” Shelby admitted. “But I’d do it all again,” she adds.

Despite the technical challenges and physical demands, there were plenty of lighthearted moments on set as well.

Bill Murray’s Antics

Bill Murray was known to be an unpredictable presence on set, providing some much-needed levity during the intense production process. One day, he arrived at the effects shop. “I didn’t realize how tall Bill Murray is (he’s 6’ 2”),” says Siegel. “And he was messing around with Robin, who’s tiny (4′ 11″), and he was picking her up like a child, and dancing around with her. He was hilarious.” For Shelby it was a surreal moment, “I was a big Saturday Night Live fan, I still am. And so he was one of my heroes at the time…so it was pretty amazing…. He asked if he could pick me up. And he picked me up over his head…. He was actually very sweet to me. You just never knew what he was going to do next.”

Effort vs. Outcome

With the crew rehearsals helping them find the limitations of the suit and the animatronic head, they began to hone the performance with some impressive results.

As Tim Lawrence told Cinefex, “Once we saw the subtlety of the expression that was possible, Slimer suddenly had an incredible life to him that I had never seen in such a character before. To see his face light up from very sad to very happy was a wonderful thing. The scene I was most happy with was one that they just threw at us. I wasn’t sure we could even do it because it was a 30-second shot without a cutaway. In it, Louis gets off the bus and heads off down the sidewalk. At this point, Slimer and he are on friendlier terms. Suddenly, Slimer enters frame, rushes intently up to Louis and pats him on the shoulder. From his motions, it is obvious he wants to go with Louis really badly, but Louis tells him he can’t and Slimer gets all sad. Then Louis tells him something that makes him happy, and Slimer gives Louis a big wet kiss with his tongue coming out and licking him. Then he does a spin and flies off. Well, we did that all in one cut and it looked wonderful. I had never seen a rubber character do what Slimer had done.”

“For that scene, they gave me a tape of it because it was shot in New York. And I had to listen to the dialogue so I could know the exact timing. I had probably listened to that hundreds of times just to get Rick Moranis’ dialogue and timing,” explains Shelby.

“Michael just flipped – he thought the performance was excellent. But at the same time, he told us that they might not be able to use the shot – and ultimately it did not make it into the film,” Lawrence had noted.

Despite completing all of the storyboarded shots, Slimer’s role in the final cut of the film was indeed scaled back considerably. Gross again explained in Cinefex: “Whenever he was in there, it seemed like he was really an intrusion. At first we thought the answer was to add more of him, so we had an ongoing confrontation between Louis and Slimer in which Louis was constantly trying to catch him. We thought it would be funny and at screenings we expected the audience to cheer and laugh when they saw him again. But nothing. No reaction. The audience was looking at it as a fresh movie. There were a lot of kids who loved to see him, so we knew we could not abandon him completely, but he never really worked with the audience the way we expected. Ultimately we decided less was better, and in the final film we limited him to two very quick shots.”

Siegel takes a philosophical approach, “From my own experience working in the business as long as I have, I just assume that some of the work’s gonna be cut…. His presence in the movie was questionable from the beginning. So again, I wasn’t surprised if some of his shots were removed.”

The disappointment is palpable for Shelby. “I think that’s probably the most bummed out I was…. Everybody just did such a great job on putting that all together.” But for the 20-year-old, little did she know that one day she’d get a call from Paul Feig to reprise the role in the 2016 reboot Ghostbusters: Answer the Call, this time providing the voice for “Lady Slimer.”

A Legacy of Experimentation

The experience of working on Ghostbusters 2, was always about the spirit of experimentation. Slimer’s evolution from the chaotic “ugly little spud” in the original Ghostbusters to a more cartoonish, mechanized character in Ghostbusters 2 stands as a testament to ILM’s relentless pursuit for innovation. Despite the technological limitations of the time, Slimer’s creation helped pave the way for future advancements in animatronics and practical effects. As Siegel concludes, “Every project has its challenges, but the lessons you learn set the stage for the next big breakthrough.”

While ILM pushed the envelope with cutting-edge animatronics, the process also highlighted the enduring importance of human performers. As Coulter reflects, “We overreached a bit. The software itself was very rudimentary. Everything was so experimental back then.” He highlighted that, despite the ability to program precise facial movements, human performers remained more adaptable and agile in responding to the creative needs of a scene. “At one point they brought the director and he looked at it and kind of went, ‘Could you make him incredulous at this one point?’ Er…. We don’t have an incredulous button here. It’s like turn the computer off, bring the puppeteers back in, and off we go again. A computer is not going to have any idea how to convey anger or emotion,” Coulter remarks, noting that even today, animators still rely heavily on human actors for motion capture, using them as the source for animation.

An Ongoing Partnership Between Practical and Digital

ILM’s current director of research and development Cary Phillips explains that physical puppets still hold a vital role in modern productions. “We often get called on to build digital models of physical puppets that perform on set, to execute performances that the physical models can’t. Grogu [from The Mandalorian] is a recent example. Physical models are an inspiration for the actors and everyone on set, as well as for animators who bring the digital version to life.”

He adds that some directors also prefer digital puppets that retain the movement style of their physical counterparts. “I think our human eyes are attuned to certain qualities of movement that we find appealing and comfortable because they suggest a physical medium at work. But that’s done by hand; there’s usually no automatic connection between the physical model and the digital.”

The challenge remains how to make a puppet, digital or physical, feel alive. “A frequent criticism of computer animation, sometimes legit and sometimes not, is that it can look too polished and smooth,” says Phillips, “lacking the spontaneity of a live performance, the unintentional quirks that make a character seem alive. Great animators can create this, but it’s hard. That’s one of the lasting appeals of motion capture, although it also introduces an entirely new set of technical challenges and limitations. Ideally, capture devices are simply an alternative to the keyboard and mouse as a way of describing movement, for use when appropriate.”

Phillips further reflects on the legacy of those who came before him and the evolving boundaries, or lack thereof, in modern visual effects. “Discovery is a vital part of the creative process. Something might feel like a mistake while it’s happening but turn out afterwards to have an appealing quality. The best tools let artists experiment quickly and work iteratively. One of the benefits of a computer graphics model is that it can do things that a physical model can’t, and we often get asked to make models and characters move in ways that violate the laws of physics. Leap tall buildings in a single bound. Cheat to get the action in the frame. So, there are no absolute boundaries—you can make it do anything. Even move in a way that would rip a real person apart. It’s an awesome power, but it takes real artistry to keep it looking plausible and appealing, even if it doesn’t look technically ‘real.’”

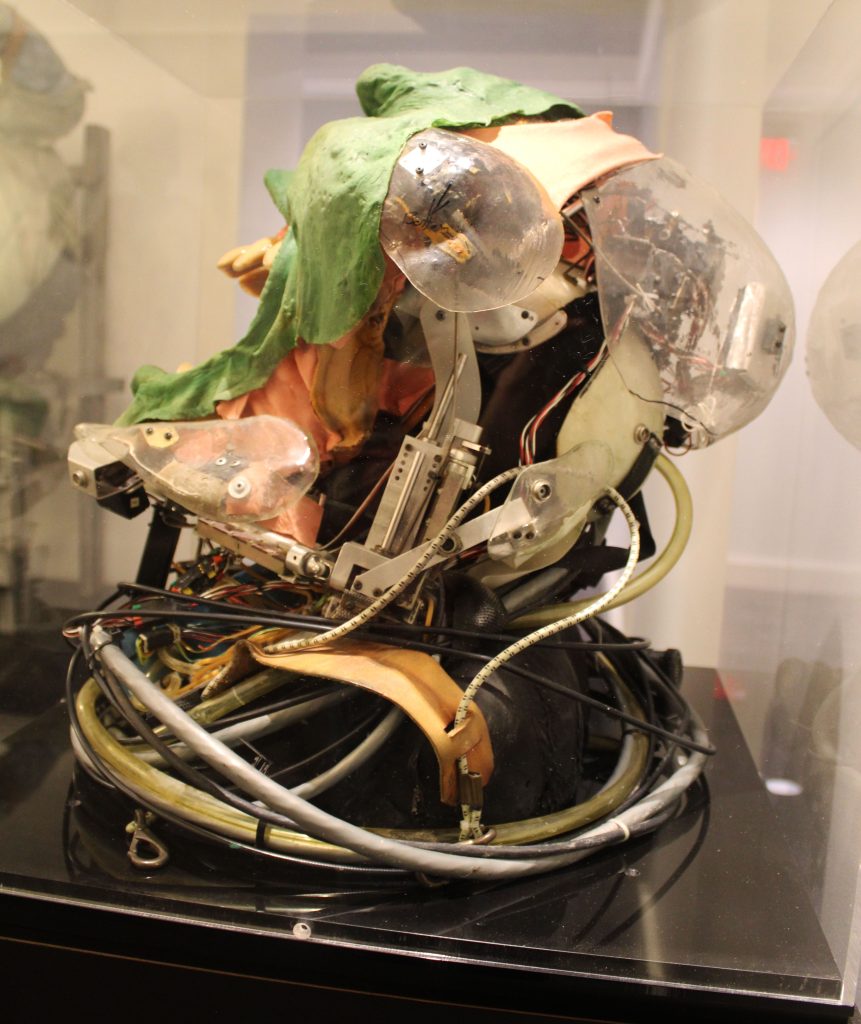

At Lucasfilm and ILM’s headquarters at the Presidio in San Francisco are halls lined with artifacts from the company’s rich history—matte paintings, spaceship models, and optical effects equipment. And around one corner, encased in acrylic, lies Slimer from Ghostbusters 2. His still vibrant green latex skin, now shrunken with age, reveals the servos and pneumatic cylinders beneath. It serves as a poignant reminder to all who pass by that character animation has deep roots in the physical world.

–

Jamie Benning is a filmmaker, author, podcaster and life-long fan of sci-fi and fantasy movies. Visit Filmumentaries.com and listen to The Filmumentaries podcast for twice-monthly interviews with behind the scenes artists. Find Jamie on X @jamieswb and as @filmumentaries on Threads, Instagram and Facebook.